-40%

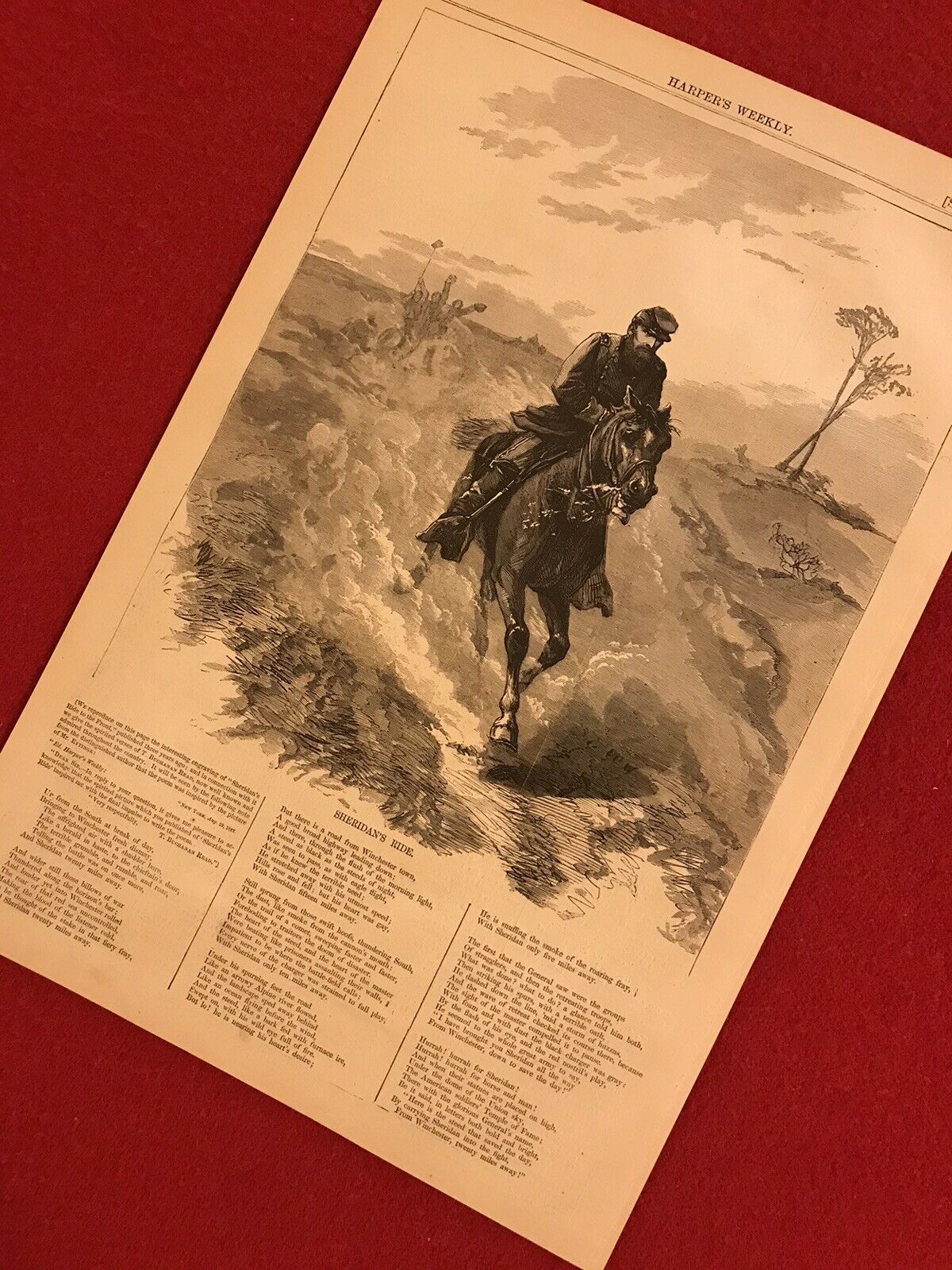

Harper's Weekly "Sheridan's Ride" ORIGINAL Engraved Page (September 14, 1867)

$ 9.24

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

Harper's Weekly (Civil War) “

Sheridan's Ride”

September 14, 1867.

Engraving and Poem!

ORIGINAL ENTIRE PAGE! (Printed on both sides.)

10 1/2” x 15 1/2 “

(NOTE: he image of the engraving itself is 9 1/4” x 11”) Worthy of framing!

Absolutely Mint condition!!!

Engraving and Poem by Thomas Buchanon Read commemorating

General Philip H. Sheridan’s

“Ride”

to rally his routed troops at the

Battle of

Cedar Creek

and

Belle Grove

(October 19, 1864).

“Jumping my horse over the rails, I rode to the crest of the elevation, and there taking off my hat, the men rose from behind the barricades with cheers of recognition.”

Gen. Philip H. Sheridan

*****

The Poem

“Hurrah! hurrah for Sheridan,

Hurrah! hurrah for horse and man!

And when their statues are placed on high,

Under the dome of the Union sky,

The American soldier’s Temple of fame,

There. with the glorious general’s name,

Be it said, in letters both bold and bright;

“Here is the steed that saved the day

By carrying Sheridan into the fight,

From Winchester - twenty miles away!’”

Although

Thomas Buchanan Read

’s poem, “

Sheridan’s

Ride

,” takes some liberties with the facts -

Sheridan

only rode some twelve miles to reach his army, not twenty - in other ways the poem is justified in honoring the Union general who turned the tables on his Confederate counterpart. Leaders like that are rare.

The Ride

Having returned to Winchester from his strategy conference in Washington, D.C., the evening of October 18,

Sheridan

retired to bed, no doubt believing that all was well with his army camped along

Cedar Creek

to the south. He anticipated sleeping late the morning of

October 19, 1864

, but around 7:00 a.m., Sheridan was awakened by an officer who had been on picket duty and heard artillery fire to the south. Initially

Sheridan

waved him off - a reconnaissance-in-force had been ordered that morning, so the fire the officer heard was because of that.

Sheridan

tried to get back to sleep, but apparently was concerned, and soon got up, and - with artillery fire still heard - determined to return to the army.

Around 9:00 a.m.,

Sheridan

, riding his horse,

Rienzi

, followed by his aides Major George A. “Sandy” Forsyth and Captain Joseph O’Keefe, and an escort of some twenty troopers, started off south.

Even after three years of war, with armies from both sides tramping up and down the

Shenandoah Valley

, the Valley Pike provided a good macadamized surface. Ruts created by the passing of artillery and wagons were avoided, and

Sheridan’s

small entourage made good time.

“It was a golden, sunny day that had succeeded a densely foggy morning,” Sandy Forsyth wrote later, but it wasn’t long before they came on supply wagons heading north. Ordered to halt and await further instructions,

Sheridan

and his staff members rode on. But now it was apparent that something had gone wrong. Soon they came on more evidence of a Federal retreat, “now and then a group of soldiers...the first driftwood of a flood just beyond and soon to come sweeping down the road,” Forsyth recalled.

By then

Sheridan’s

face had taken on a determined look; he was aware that a disaster of some proportion had befallen his army. When the general saw groups of soldiers, “sitting or lying down to rest by the side of the road, while others were making coffee,”

Sheridan

vigorously waved his hat to the front, calling for them to “Turn back, men! Turn back! Face the other way!” Most of the soldiers did just that, and all broke into cheers “

Sheridan! Sheridan!”

at the sight of their leader.

“...the appalling spectacle of panic…"

A few miles more, they reached Newtown (Stephen’s City today), where they found a field hospital, ambulances in abundance, and wounded men all around. Here

Sheridan

, Forsyth and O’Keefe – their cavalry escort had been left behind - left the pike briefly, rode through a small wooded area, and up a slight hill. Reaching the top of that rise, Sheridan later described the scene:

“there burst upon our view the appalling spectacle of panic...hundreds of slightly wounded men, throngs of others unhurt but utterly demoralized, and baggage wagons by the score, all pressing to the rear in hopeless confusion, telling all plainly that a disaster had occurred at the front.”

About 10:30 a.m., they reached the army, then positioned 1.5 miles north of Middletown. One of the first officers they met, Colonel Amasa Tracey, commanding the Vermont Brigade, saluted

Sheridan

: “General, we’re glad to see you,” Tracey said. “

Well, by God, I’m glad to be here. What troops are these?”

“Sixth Corps! Vermont Brigade!” the soldiers nearby yelled, delighted to see their commanding general among them again.

“All right, we’re all right!” Sheridan’s reported to have said. “We’ll have our camps by night

!”

Worth 10,000 reinforcements

Sheridan’s

return marked a turn-around in the battle. One Union officer would later state that his arrival was worth more than 10,000 reinforcements, and indeed, it seemed so. After reorganizing his lines,

Sheridan

rode the length of them, and “his appearance was greeted by tremendous cheers from one end of the line to the other, many officers pressing forward to shake his hand.” He then planned for a counter-attack. Launched at 4:00 p.m., the assault was initially met with stiff resistance, but by the end of the day the Federals had driven the Confederate army from the field.

Sheridan’s

timely arrival and inspirational leadership had turned a certain defeat into a momentous Union victory.

*****

The Author

Thomas Buchanon Read

(1822-1872) was a relatively minor artist and poet of the nineteenth century, but he did have one very enduring success during the Civil War. Read’s 1864 poem

“Sheridan’s Ride”

, which celebrated Union general

Philip Sheridan’

s rallying of his soldiers at the

October 19th, 1864

Battle of Cedar Creek

in

Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley

, was widely published and served to promote the success of the Union war effort and President Abraham Lincoln’s reelection in that election year.

In August of 1864,

Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant

ordered

Major General Sheridan

to conduct a campaign against

General Jubal Early’s

Confederate Army

operating in the

Shenandoah Valley

. Sheridan was also to neutralize the Valley as an economic resource to the Confederate army by destroying crops, railroads, and anything else of value to the Rebel cause. Moving tentatively at first with only minor fighting and skirmishing, Sheridan picked up the pace with a major engagement at the

Battle of Opequon, or Third Winchester

, on September 19th, followed by the

Battle of

Fisher’s Hill

on the 21st and 22nd, and the

Battle of Tom’s Brook

on October 9th. Each of these was a Union victory.

Sheridan was confident that Early’s force had been reduced to the point that it was no longer a major threat. The Federals sent up camp along the banks of Cedar Creek and the commanding general went to Washington DC to discuss future plans and strategy. After departing Washington, Sheridan spent the night of October 18th at Winchester. Meanwhile, Early and his generals planned a surprise attack on the Union encampment. In the predawn hours of October 19th, the Confederates attacked, taking the Federals by surprise and routing two Union corps.

Sheridan awoke that morning and heard the distant cannon fire of the battle. He hopped on his horse named

Rienzi

and rode south toward Cedar Creek

As he approached the battlefield, Sheridan saw much of his demoralized army in retreat heading north. His commanders filled him in on the situation, and Sheridan proceeded to rally his troops, turning them around and restoring morale. Launching a counterattack that afternoon, the Federals turned almost certain defeat into victory.

Within days,

Thomas Buchanon Read

wrote a poem commemorating the ride from Winchester to Cedar Creek (though historians note the distance from Winchester to Cedar Creek was more like 12 miles and not the 20 in the poem). The poem was an immediate hit; Sheridan himself liked it and

changed Rienzi’s name to Winchester

. The ride was also celebrated in paintings, including one by Read himself; Sheridan, mounted on Rienzi/Winchester, posed for Read in 1865. After his death, Winchester was preserved by taxidermists and can be seen today at the

Smithsonian

Institution’s National Museum of American History.

*****

Sheridan

At war’s end,

Phil Sheridan

was a hero to many Northerners.

Gen. Grant

held him in the highest esteem. Still, S

heridan

was not without his faults. He had pushed Grant’s orders to the limit. He also removed Gettysburg hero Gouverneur Warren from command. It was later ruled that Warren’s removal was unwarranted and unjustified.

During

Reconstruction

, Sheridan was appointed to be the

military governor of Texas and Louisiana (the

Fifth Military District

). Because of the severity of his administration there,

President Andrew Johnson

declared that Sheridan was a "tyrant" and had him removed.

In 1867,

Ulysses S. Grant

charged Sheridan with pacifying the Great Plains, where warfare with Native Americans was wreaking havoc.

In an effort to force the Plains people onto reservations, Sheridan used the same tactics he used in the Shenandoah Valley: he attacked several tribes in their winter quarters, and he promoted the widespread slaughter of American bison, their primary source of food.

In 1871, the general

oversaw military relief efforts during the Great Chicago Fire

. He became the

Commanding General of the United States Army

on November 1, 1883, and on June 1, 1888, he was promoted to

General of the Army of the United States

– the same rank achieved by

Ulysses S. Grant

and

William

Tecumseh Sherman.

Sheridan is also largely

responsible for the establishment of Yellowstone National Park

– saving it from being sold to developers.

In August 1888, Sheridan died after a series of massive heart attacks. He was buried at

Arlington National Cemetery.

****

The page will be shipped in a hard mailing tube.